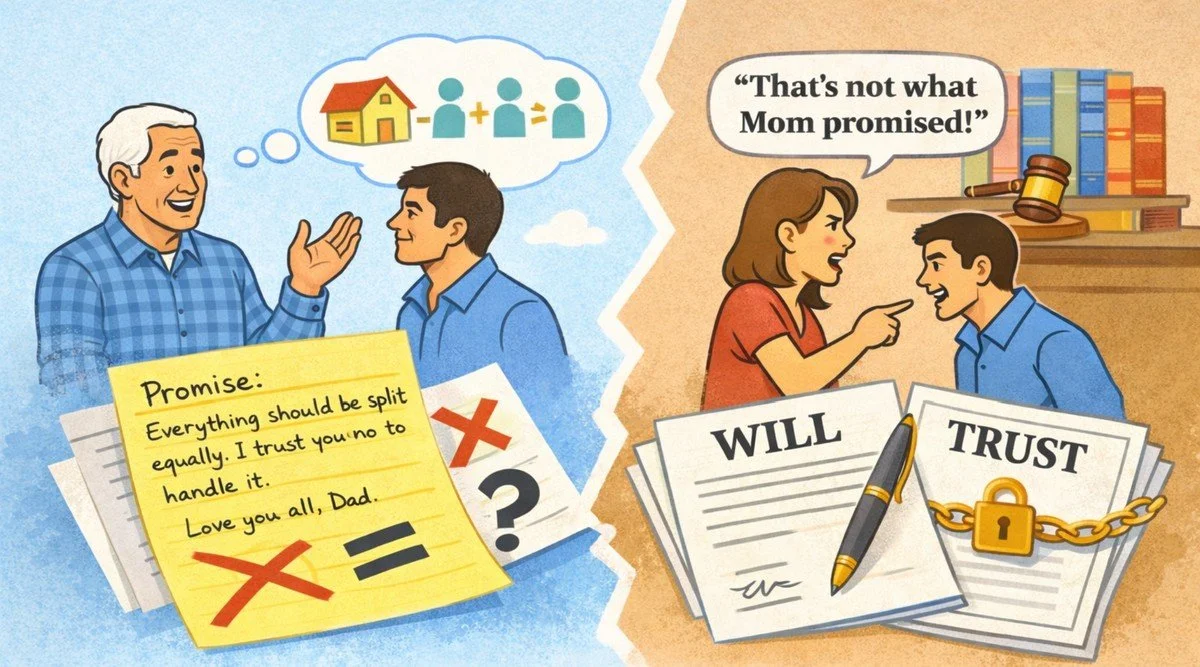

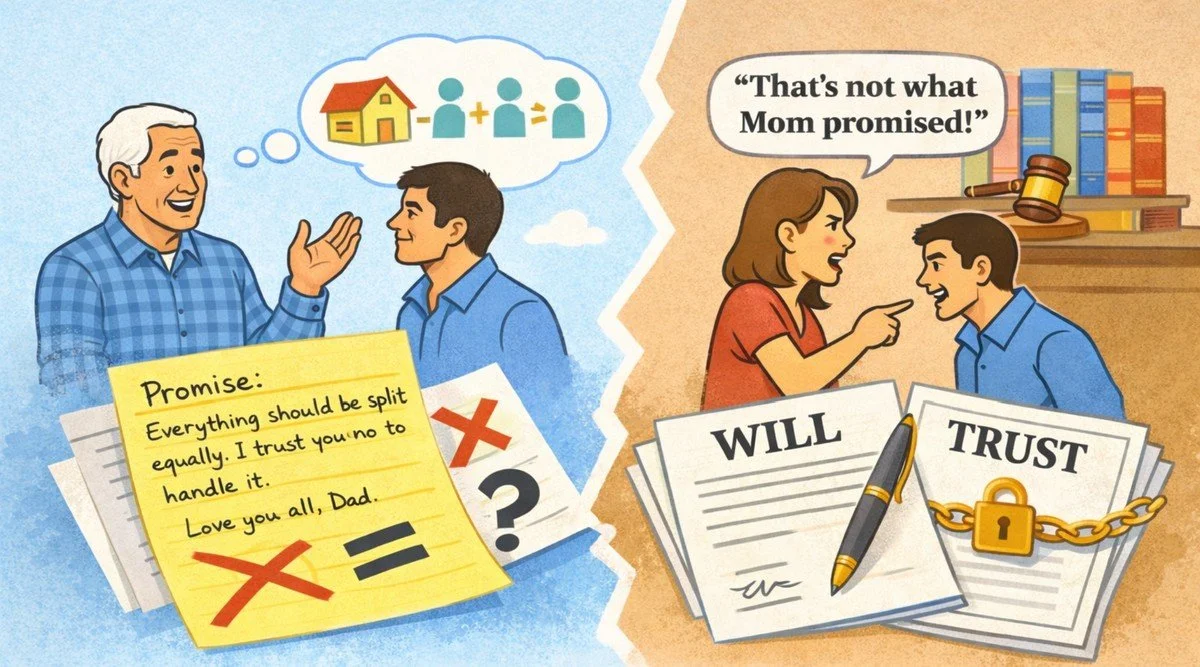

A Promise Means Nothing Until It’s in Writing — And Even Then, It Can Often Be Changed

Verbal promises don’t make for reliable estate planning

Estate planning disputes rarely begin with bad intentions. More often, they begin with a sentence like:

“That’s not what Mom promised.”

Promises, assurances, and family understandings feel powerful while everyone is alive and communicating. But when a person dies, the legal system does not enforce memories, conversations, or expectations. It enforces documents—and only certain kinds of documents.

Even then, many people are surprised to learn that most estate planning documents are revocable during life. Until death occurs, intentions can change, documents can be revised, and promises can be undone. Understanding this reality is critical to avoiding confusion, resentment, and litigation.

Table of Contents

- Why Verbal Promises Have No Legal Effect

- Handwritten Notes, Emails, and Informal Writings

- Example: “I Told You the House Would Be Yours”

- Why Courts Enforce Documents, Not Intentions

- Most Estate Planning Documents Can Be Changed

- Example: The Will That No Longer Reflected Reality

- The False Sense of Security Promises Create

- Example: One Child “In Charge”

- How Promises Lead to Family Litigation

- What Proper Estate Planning Actually Accomplishes

- When to Speak With an Estate Planning Attorney

Why Verbal Promises Have No Legal Effect

Verbal promises, no matter how sincere, do not control the distribution of assets after death. Courts do not enforce conversations, dinner-table assurances, or repeated statements of intent.

Common examples include:

- “The house will be yours someday.”

- “You’ll all be treated equally.”

- “Don’t worry, I already took care of you.”

While these statements may guide family expectations, they carry no legal authority. When a dispute arises, judges do not attempt to reconstruct conversations. They examine executed documents—or, if none exist, they apply default inheritance laws.

Handwritten Notes, Emails, and Informal Writings

Families are often shocked to discover that handwritten notes, emails, or unsigned letters typically have no legal effect. A note in a desk drawer or a message saved on a phone rarely meets statutory requirements for a valid estate document.

Even when a writing is clearly in the decedent’s handwriting, courts are cautious. Without proper execution formalities, such documents are often disregarded entirely.

This disconnect between expectation and enforceability is a common source of conflict. Family members may rely on informal writings for years, only to learn after death that they are meaningless.

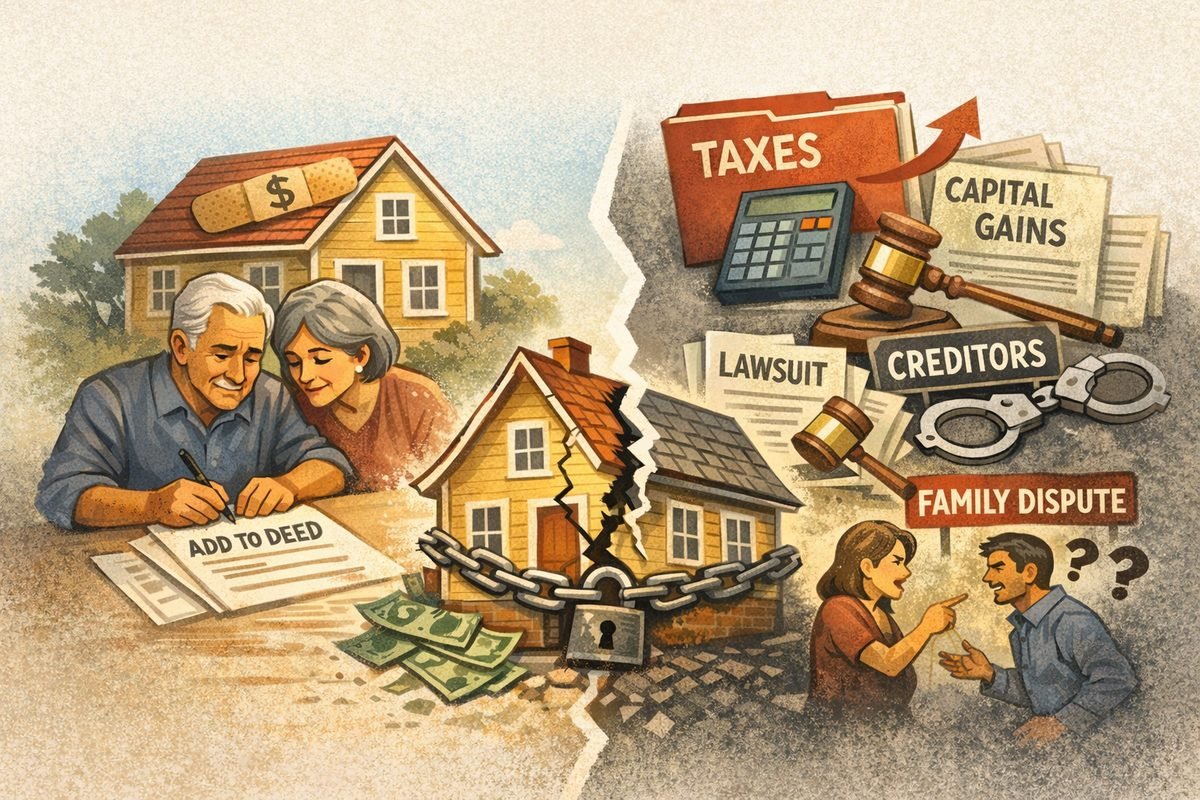

Example: “I Told You the House Would Be Yours”

Consider a common scenario:

A parent tells one child repeatedly that the family home will eventually be theirs. That child helps with maintenance, pays some expenses, and assumes the house is effectively “spoken for.”

At death, the parent’s will leaves the estate equally to all children. The house must be sold to divide the proceeds.

The child who relied on the promise feels betrayed. The siblings insist they are simply following the will. From a legal standpoint, the will controls. From an emotional standpoint, the damage is lasting.

Why Courts Enforce Documents, Not Intentions

Estate planning law is intentionally rigid. Once someone has died, they cannot clarify what they meant or correct misunderstandings. Formalities exist to prevent fraud, coercion, and guesswork.

As a result:

- Only properly executed documents are enforceable

- Only the most recent valid document controls

- Only what is written matters

Courts do not rewrite estate plans to make them fair. They apply them as written, even when the outcome is harsh or unexpected.

Most Estate Planning Documents Can Be Changed

Another widespread misconception is that once a will or trust is signed, it becomes permanent. In reality, most estate planning documents are intentionally revocable during life.

In many cases:

- Wills can be revoked or replaced at any time

- Revocable trusts can be amended repeatedly

- Beneficiary designations can be changed with a form

This flexibility allows plans to evolve as families and finances change. But it also means that a promise— even one reflected in an older document—may not survive later revisions. Only the final, valid version controls.

Example: The Will That No Longer Reflected Reality

A client prepares a will shortly after the death of a spouse. At the time, the plan makes sense. Years later, relationships change, finances shift, and priorities evolve.

The client talks openly about “updating things someday” but never does. Family members rely on conversations, not realizing the documents remain unchanged.

At death, the old will governs. The result surprises everyone—and no amount of testimony about conversations changes the outcome.

The False Sense of Security Promises Create

Promises create certainty where none exists. A child who believes they are protected may make financial or personal decisions based on that belief. Other family members may remain silent, assuming everything is settled.

When the documents tell a different story, the realization often comes too late. By the time the truth emerges, the person who could have fixed the misunderstanding is gone.

Example: One Child “In Charge”

Parents sometimes tell one child they will “handle everything” and “take care of the others.” That chil